You probably have seen Newton's Cradle in science class, and perhaps you have one at home, too. Pull the ball at one end, let go and let it strike the next ball, and lo and behold the ball at the opposite end swings out. Pull two balls, and two balls swing out.

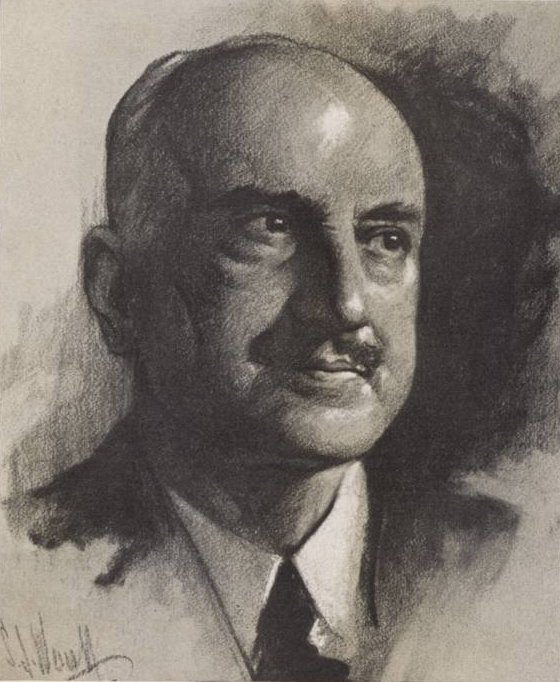

Whether you’ve heard of them or not, two gurus from the early twentieth century still dominate management thinking and practice — to our detriment. It has been more than 100 years since Frederick Taylor, an American engineer working in the steel business, published his seminal work on the principles of scientific management. And it has been more than 80 years since Elton Mayo, an Australian-born Harvard academic, produced his pioneering studies on human relations in the workplace. Yet managers continue to follow Taylor’s “hard” approach — creating new structures, processes, and systems — when they need to address a management challenge. Hence, the introduction of, say, a risk management team or a compliance unit or an innovation czar. And when managers need to boost morale and get people to work better together, they still follow Mayo’s “soft” approach — launching people initiatives such as off-site retreats, affiliation events, or even lunchtime yoga classes. If these approaches made sense in the first half of the twentieth century (and that’s open to question), they make no sense today. Indeed, if anything, their continued use is making things worse.

Reference:

Stop Trying to Control People or Make Them Happy.

What Yves Morieux and Peter Tollman, from The Boston Consulting Group, speak to is a veritable pendulum swing à la Newton's Cradle.

One company set up programs, launched initiatives, and even underwent a reorganization. Whether it was a sales academy or a business restructuring, project leaders imposed an idea on people and then, quizzically, sought to engage and motivate them on the idea.

One manager, bereft of ideas in general, occasionally suggested lunch outings and fun retreats. The idea was to make the people feel better about working there and hitting targets.

Oddly enough, on both counts, people were the forgotten figures. Moreover, there was insufficient examination (analytic) and reflection (intuitive) on the actual factors, issues or causes that gave rise to people's frank dissatisfaction and under-performance. It is an organizational crime, I argue, for any leader to coax cash out the budget for an initiative that is fundamentally off or flawed from the get-go. It is a crime when that leader is unusually persuasive or aggressive, and can get people to comply.

Things can prevent the sort of examination and reflection necessary. For the company, it was ineptitude. Senior managers simply didn't know how to relate to people, inquire about their issues, and work at resolving them. For the manager, it was abusiveness. He was a hostile, self-absorbed sort, who had tin ears for more nuanced, unspoken issues among people in the office.

In each case, there were attempts at Frederick Taylor and Elton Mayo efforts, so their Newton's Cradle swung like pendulums from one end to the other. People were simply balls in the middle that absorbed the force, then transmitted it, but never really went anywhere.

I scoff at simplistic advice, in the way that Morieux and Tollman set out to do and announce explicitly in the title of their book. Be that as it may, I appreciate their first rule: that of understanding people as best as possible.

If you are the CEO, efforts begin with your (i.e., the organizational) end in mind. Purpose or aim is the guidepost for how to look at factors, issues and causes. People are an inevitability in any organization, so they must be engaged and motivated, not as a matter of consequence, but as an agent of change and resolution.

Understand them in the truest, deepest possible way.

Thank you for reading, and let me know what you think!

Ron Villejo, PhD